In the mid-1800s, a number of luthiers emerged that set new, higher standards for the zither. With this continued refinement, the zither began to play a more important role as new players, teachers and clubs began to emerge. In this article, Dr. Joan Marie Bloderer provides a biographical sketch of three early zither makers from Mittenwald, whose efforts led to significant improvements and worldwide recognition of this instrument.

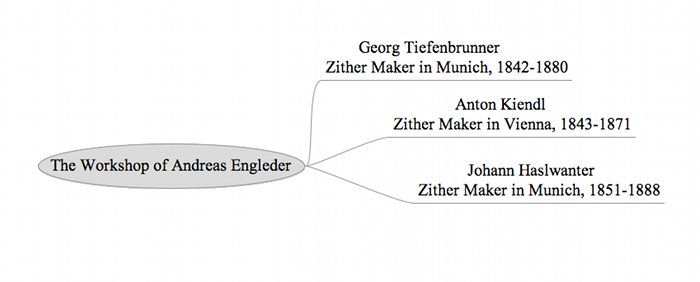

Who would suspect that the first three zither makers to gain world fame had once been neighbors? Yet Georg Tiefenbrunner (1812 - 1880), Anton Kiendl (1816 – 1871) and Johann Haslwanter (1824 - 1884) were all born within 12 years of each other in or near the alpine village of Mittenwald. Mittenwald’s centuries old fame rests of course on its violin production. That it later became a production center for the (at that time rather lowly) zither is an interesting story we’ll get into another time. For now, let it be said that there was considerable expertise in stringed instrument making in Mittenwald at the beginning of the 19th century. Thus, it was not just by chance that the three first outstanding zither makers grew up there.

Tiefenbrunner, Kiendl and Haslwanter zithers are among the acoustically finest ever made. A brief look at their early lives will show that they reached this excellence along very different paths.

Georg Tiefenbrunner was born in Mittenwald in 1812, six years after Bavaria had been transformed from a duchy into a kingdom. Napoleon still dominated the political scene in Europe, and it was just seven years since little Mittenwald had been a scene of conflict, under constant harrassement to deliver supplies (food, rooms, horses) to whichever army happened to be in the vicinity.

Tiefenbrunner was a common family name among the violin makers in Mittenwald at that time. Georg, very likely, spent all his afterschool hours in one of the family or neighboring violin workshops, engaged in all the little tasks Mittenwald boys were then responsible for: carrying, stacking, varnishing (the first coats), polishing, keeping the fire in the stove going, hanging up the violins outside to dry, etc. He learned a lot. Of course he wanted to become a violin maker. But he went into apprenticeship not in Mittenwald, but in Landshut, north of Munich. His master was probably Lorenz Kriner, an excellent craftsman who had been born in Mittenwald himself. Georg later worked in the shop of one of the finest violin makers of the day: Andreas Engleder, in Munich. Here his path crossed that of Anton Kiendl (see below), who took his mastership in Engleder’s workshop. Engleder made some beautiful zithers around this time, some of which may actually have been made by Tiefenbrunner or by Kiendl, with Engleder’s label (as shop master) glued inside. Georg took his mastership as a violin maker in Augsburg.

At the beginning of the 1840s, Tiefenbrunner married the daughter of a Munich shop keeper, who sold just about everything, including shoe polish, salt, simple zithers and violin strings (that he made himself). Tiefenbrunner’s father-in-law, Franz Kren, possessed a license to maintain this kind of a shop in the middle of Munich. With his marriage, Tiefenbrunner acquired the right to continue running the shop when his father-in-law retired. In those days, resorting to marriage was one of the few means open to poor, talented craftsmen which assured them the right to a workshop within the city (these being otherwise controlled by the strictly limited guilds). And indeed, Tiefenbrunner took over the Kren family business in 1842. For reasons we’ll have to explain another time, this was perfect timing in an almost-perfect place. Tiefenbrunner’s excellent zithers (and those of his son and grandson) are admired today not only for their sound, but also for their painstaking craftsmanship. In many respects they closely resemble those made by Anton Kiendl. But first to Johann Haslwanter....

Johann Haslwanter was born in 1824 in a village near Mittenwald, perhaps in Krün or Wallgau,. His father was a woodcutter in a nearby Austrian village. His mother’s sister was married to the one and only zither maker in the suburbs of Munich, Ignaz Simon (from Mittenwald, of course). Ignaz Simon differed from Tiefenbrunner’s father-in-law Kren, in that he seriously tried to improve on his admittedly simple instruments. This may have been a result of his having to cater to some very demanding customers, the Austrian zither virtuoso Johann Petzmayer and his employer and friend Duke Maximilian (the future father of Elisabeth, Empress of Austria).

Haslwanter most likely was sent to live with his uncle at a very early age. He virtually grew up in Simon’s workshop, which must have been a very lively place, buzzing with activity and conversation. Most of the zither players in greater Munich went in and out. (This was the 1830s, and Tiefenbrunner, around 20, was still getting his own education.) There were hot debates concerning the lowly zither, which needed not only a better reputation but also a more refined method of construction.

Johann Haslwanter purportedly showed enormous aptitude for wood craftsmanship at an early age. He must have known Anton Kiendl (yes, we’re getting to him soon), who was among the very frequent visitors to the Simon shop, and who was already a fine craftsman himself. Simon gave his nephew the best education he could, which meant apprenticing him to Andreas Engleder (in whose shop both Tiefenbrunner and Kiendl had worked). After gaining his mastership, Johann took over the workshop from his uncle, who had by now passed the age of 60. Shortly after 1850, Haslwanter relocated the shop just a short distance away within the boundaries of Munich proper. Although 12 years younger than Tiefenbrunner and a paltry 8 years younger than Kiendl, he profitted from the great zither expertise that had surrounded him as he grew up and from the enormous progress that zither-making had made during the 1840s. He may be looked upon as a member of the „second generation“ of modern zither makers. Johann Haslwanter (and later his son Johann Otto) crafted excellent zithers that were in great demand for decades. He also suggested improvements in the spinning of strings, eventually publishing a small book on the subject.

Anton Kiendl had a unique childhood in comparison to his „neighbors“ Tiefenbrunner and Haslwanter. He was born in 1816 in Mittenwald as the son of the local school master. In those days, the persons of greatest respect in Bavarian country life were the local priest, the mayor, the keeper of the largest inn, and — the school master. Kiendl’s father gave him the best education he could, by sending him off after grammar school to his uncle, a high school teacher in Innsbruck. In those days, high school amounted to a sort of „higher education.“ Kiendl seemed destined to follow in his father’s footsteps as a teacher. For some reason not known to us, young Anton (who was never of particularly good health) decided to become a violin maker instead. This must have created a small earthquake in the Kiendl family. Anton would have seemed to have had everything against him: not being the son or relative of a violin craftsman (or a craftsman at all, for that matter), he would hardly have been allowed access to one of the traditional and – for outsiders — rigorously secretive workshops. Who would take the trouble to invest time and patience in a not very well-to-do teenager with a „bookish“ background and without the experience of the other boys in the Mittenwald violin maker‘s shops? We don’t know the answer completely. We do know that he gained some kind of an obviously careful training in the rudiments of the craft, but only one private memorandum mentions the probable surname of his Mittenwald master.

Anton Kiendl actually first emerges as a violin craftsman during his sojourn in the Munich workshop of Andreas Engleder. During those years (we assume the late 1830s, at the end of his teens) he was influenced not only by the skilled and impeccable Engleder himself, but also by the activities in the Simon workshop outside the city, where the young Johann Haslwanter was already showing promise. Kiendl took his mastership as a „violin maker“ around 1842. (Although by this time Kiendl was already concentrating almost completely on the zither, „zither maker“ wasn’t a recognized profession). Kiendl returned to his family in Mittenwald. Here he must have sensed the futility of setting up a country workshop, perhaps because the demand on zither makers outside the city of Munich was extremely limited. Farmers often made their own instruments, and Mittenwald violin makers still concentrated on making violins, even though the violin market had since pretty much collapsed. There were no Mittenwald workshops specializing in zithers and almost no customers demanding good ones. Kiendl was by this time, the father of a daughter, and this responsibility spurred him on to make a proper living. His choice fell on Vienna. He had relatives there, and his experience with Munich may have contributed to his belief that a workshop in the city would guarantee a suitable livelihood. But he was wrong, at least in the beginning. As he wrote to his family, the situation for zither makers in Vienna was devastating. There was no demand, there were no customers. He would have returned to Mittenwald immediately if he’d had the means, but his move had cost him all of his savings. This was enormous luck for the zither world! Anton Kiendl was forced to stay in Vienna. In the process of creating an income for himself, he created a market for the zither (for the sophisticated instruments he built) almost single-handed. „Almost,“ because early on he went into a business liason with Carl Umlauf, a rather flashy zither entertainer with a gift for showmanship and for winning pupils. Kiendl and Umlauf complemented each other perfectly. Kiendl boosted interest in the zither by circulating the zither teaching manual that Nikolaus Weigel had published in Munich in 1838. He kept close contact with the Viennese zither players (few and far between, they were mostly entertainers) and worked exceedingly hard at improving his instrument. Umlauf was good for numerous contacts among the Viennese upper middle class, teaching many of them and playing regularly in their private salons. Kiendl also created a salon of his own, where the few zither personalities of the city gathered on Sunday evenings in the winter months. As usual, luck played a part. Other circumstances had already sparked an interest in the zither among the Viennese middle and upper classes. Because the wonderful Kiendl instruments were available, this interest could deepen and take root, resulting in a whole new cultural business: the zither business. Manuals were published, teachers appeared, concerts were heard, zither music was sold, new zither makers became active.

Anton Kiendl’s health was soon damaged, however, by his constant activity in cold, drafty rooms, engaged in the concoction of varnishes, glues and other tasks. Somewhere during the 1850s, we think, he lost his sight in his left eye when it was pierced by a breaking string. The enormous energy he had invested in his very successful firm took its toll early. Soon after the marriage of his daughter Maria to the government official Matthaeus Much, Kiendl was forced to lay the fate of his company in his son-in-law’s hands. Kiendl was just 44 years old. During his remaining eleven years, he saw to the education of his nephew Karl Kiendl (born near Mittenwald). Karl became a renowned Viennese zither maker in his own right.

At the moment, we see Anton Kiendl as the „father“ of the modern zither. The zither craze that beset Vienna in the 1840s and ’50s was a direct result of his initial and unrelenting effort. With the close cultural connections then existing between Vienna and Munich, this simultaneously gave impetus to the just-budding zither workshops in Munich, those of Tiefenbrunner and Haslwanter.

We aren’t by any means finished with our research. In fact, the author is knee-deep into an investigation of the Bavarian zither and its relationship to the Viennese zither. The results will appear in book form as „The Zither in Bavaria 1830 – 1880,“ either in English or in German (I can’t promise you anything there). We’ll keep in touch.

Dr. Joan Marie Bloderer's previous work, Zitherspiel in Wien. 1800-1850, provides insight into the lives of early zither personalities, tunings of the zither and samplings of printed zither music. The reader will certainly glean new information from the significant number of never before published illustrations included with this text. For those interested in continuing their research, an extensive bibliography is also provided. For more information visit the publisher's web site at Schneider-Musikbuch.