Originally published in 1910, Frederick Francis Cook's Bygone Days in Chicago provides the author's personal recollections of Chicago in the 1860s, up to the Great Chicago Fire of 1871. Of particular interest to zitherists is the story of "Ibach", a Hungarian zither player who would perform at a bar, colloquially known as "The Sharp Corner," located at the south-west corner of La Salle and Randolph Streets. While interesting for the scene it evokes, the story also hints at our zither player's repertoire.

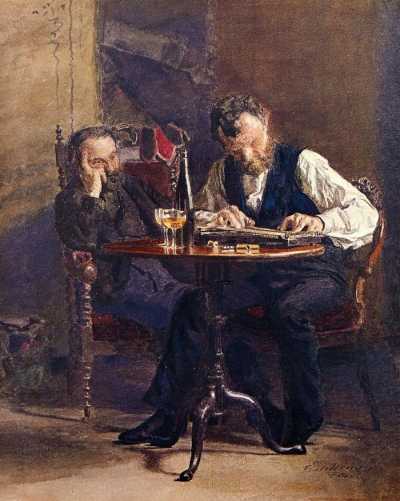

Ibach was a character and Gottlieb was another. A third factor in a notable ante-fire triune was the south-west corner of La Salle and Randolph Streets, where stood a time-worn, two-story frame house, known to the Chicago of the sixties as "The Sharp Corner." So far as the "lay of the land" had anything to do with it, this particular corner was not a whit more pointed than any other thereabout. No, the acuteness was all in Ibach and Gottlieb.

If Ibach could ever answer to a baptismal prefix it never became public property; and if Gottlieb was blessed with any sort of cognominal suffix, it remained a profound secret. Ibach was proprietor, Gottlieb factotum, and "The Sharp Corner" a Wirtschaft dear to many an old-time Bohemian, where the food was ever savory, the beer of the best, while the wine -- but that was usually more or less by the way, so far at least as we of Bohemia were concerned. However, what really counted was that Ibach played the zither, and few have touched this bewitching instrument more sympathetically -- an estimate appreciatively emphasized when in after Theodore Thomas presented him as a soloist at some of his summer-night concerts.

Ibach, a Hungarian by birth, had the musical passion of a gypsy; and when the humor of a propitious occasion reached full-tide ( best evoked by liberal libations of his most expensive champagnes ) he would play as one possessed, with eyes in fine frenzy rolling --and they were eyes to remember --his body swaying this way and that in rhythmic abandonment to some moving cadence, while big, ecstatic tears fell unheeded on his beloved instrument.

Ibach's tongue readily worked overtime; whereas Gottlieb, true to his role of foil, seldom permitted himself to go beyond a laconic "Ja Wohl." If the one exhibited himself as an embodiment of irascibility, the other stood at attention as an incarnation of imperturbability. Ibach was short and lean; Gottlieb was short also, but as rotund as a brownie, which goggle-eyed tribe he oddly resembled. The one would fume and storm on the slightest provocation, his face afire, his eyes aflame; the other held ever to a sphinx-like silence -- the placidity of his vacuous visage seldom disturbed by so much as the raising of an eyelash. Ibach's explosion's, when not touched off to order, were but the necessary escapes of an overstrung temperament; and almost as quickly as an outburst came it would subside -- only there was always another waiting its turn. In one respect only did these twin stars shine in unison -- both were preposterously bald.

Ibach held his talent as a zitherist at full value. That piercing eye of his sized up a crowd in a flash. His zither was his money-maker; and, as a rule, he would touch it only for big game -- "Board of Trade fellers" being a favorite quarry.

An habitue once remarked: "Why didn't you play for Jones and his friends the other night? They were much disappointed." "Vat? dose fellers! Pooh! Notting but beer guzzlers."

Ibach had, however, a sentimental as well as a mercenary side. With a few he was an extravagant Schwärmer; and to this kind all Saturday nights were consecrate. Then it did not so much matter if nothing more expensive than beer or wine of the Rhine was ordered; though whenever "Big Bill" Hurlbut - he of later baseball-management fame - was present ( and he was seldom absent from these Saturday night assemblies ), nothing but champagne would answer; and when, as quite frequently happened, he took advantage of his generous privileges to introduce a Philistine or two, it was understood that they came prepared to pay grand opera box prices for their share of the entertainment.

I had a friend in William Buderbach, whom a few may recall as whilom leader of McVicker's Theatre orchestra. Buderbach's physiognomy ordinarily expressed about as much animation as a wooden cigar-store sign; but beneath this inexpressive, unemotional exterior, there dwelt a soul wedded to a marvelous "Cremona," and the inspirations of the masters. One Saturday night we left the theatre together, and that gave opportunity to invite him to join the Ibach circle. Always shy and diffident, he yielded a reluctant consent; but once there, he must needs introduce his best beloved; and from that time forward, for happily many moons, Ibach and Buderbach became for us daft dreamfolk, dual well-springs of dulcet harmonies.

The elect would ingather shortly after ten, and it was always a sore disappointment to me if some untoward news event compelled me to forego any part of the golden hours. As soon as an instalment of the Burschen -- Ibach's German alternative for his English "fellers" -- put in a appearance, Gottlieb would begin manoeuvring to rid the place of all not duly accredited, by overmuch looking at the clock, and a superadded wiping of tables, thereby starting feelings of discomfort in all not of the elect. And no sooner was there a happy riddance than the door was locked, and so remained for all not provided with the magic sesame.

Sometimes in the interval form the last gathering, Ibach might have made some precious musical find, and would begin to whet our appetites for the coming feast with discourse upon his discovery. "You will hear!" he would exclaim, "it is himmlich!" -- and thus would be open by anticipation the antechamber of the the heaven to be later our possession.

Celestial rhapsody! Ah, the reader must remember the time of which this is written. Theodore Thomas, even as a visitor, was not to rise on Chicago's horizon for yet many a year; while such luminaries as Bloomfield Zeisler and Maud Powell, veritably to the manner born, were still a part of the formless void. In those days artists from elsewhere were rare birds, indeed; and almost the only indigenous music offered the general public was something on Sunday afternoons, called a Sacred Concert, at the North Clark Street Turner Hal ( and lo! they still abide ) that rang its everlasting changes on overtures to, or potpouris compounded of, the "Czar and Zimmermann," "Nabucho", "Robert le Diable," "Martha," "The Bohemian Girl," "Maritana," "William Tell," "The Merry Wives of Windsor," and a few more of this delectable company -- while what fell to our lot in the "Sharp Corner" oasis would bring joy to cultivated lover of music event today.

There were generally about a dozen for audience. A longish table was tacitly yielded to the players and such "champagners" as might be present -- i.e., Board of Trade "fellers" under Hurlbut's leading. The rest would be grouped about smaller tables, while Gottlieb, personifying silence, attended to orders. Ibach invariably sat at the head of the table, Buderbach at his left, Hurlbut at his right, and the latter's immediate friends farther down. As a matter of fact, however, the real head of the table was wherever "Big Bill" sat. He completely filled the biggest chair, and had that masterful way to which subordination is readily yielded. Besides, he would often "blow in" ( this will not appear as slang to any who recall his mighty chest emissions ) twenty dollars or more at a sitting -- the more usually depending on the turn the day's market had taken. When there was a violin accompaniment, the selection had as a rule a semi-classical flavor; but in his zither solos, with an eye strictly to business, Ibach would shrewdly fit himself to the part of his audience which divided their attention between the Muse of Music and the Widow Cliquot.

It would scarcely be true to speak of "Big Bill" as a classicist musically -- even if a whole class by himself. Nor was he, strictly speaking a romanticist -- though in an old-fashioned way chock-full of sentiment. A tender love-song of Schubert's or Schumann's might now and then evoke a grunt of appreciation; but, on the whole, he was only charitably tolerant toward the masters because others enjoyed them. What he liked better was something that had the lilt of the Tyrol, or thrilled with Magyar abandon. He was, however, never completely in his element until by easy but well calculated approaches Ibach arrived at what may be called the "Way down upon the Suwanee River" or "Come where my love lies dreaming" stage. The, and not till then, did "Big Bill" come wholly to the fore. And then, while his eyes blazed a challenge, and his transfigured jowl testified to a complete surrender to the hour, amidst a mighty heaving chest, there would be issue as from subterranean depths the incontrovertible verdict, "There's music for you!"

At this stage of the fantasia it was difficult to catch Gottlieb's eye, as, with napkin over shoulder, he stood well within range -- and there would invariably follow ( accompanied by a sweep of the arm that included the entire company ) the Hurlbutian laconic: "More wine!"

Now, from an illumined Ibach: "Gottlieb, did you hear?"

From an imperturbable Gottlieb: "Ja wohl!"

From an exasperated Ibach: "Himmel donnerwetter! Vy don't you bring it?

Eruptions at this stage of the champagne flow represented only the veriest stage thunder. Ibach knew only too well what a contrast his electrical discharges formed to Gottlieb's unshakeble immobility; and he was not above throwing in a wink and other theatrical "business" to heighten the effect.

Inscrutable Gottlieb -- was he ever caught off guard -- in a mental undress, as it were? I doubt it. And yet, on occasion when some exceptionally moving cadenza flooded all hearts to suffusion of eyes, I sometimes imagined I could detect a facial flutter as of some inmost chord, occultly touched. But it was probably an optical illusion.

Ibach's Board of Trade "Lambs," though shorn so deftly, and to such lulling accompaniment, did not always undergo the operation without suspicion of ulterior designs. Once a visitor, who had been "played" to a lively tune, turned to the maestro with the inquiry: "What do you call it when you work the strings?"

"Dey call it 'plucking' in English."

"Indeed? I was under the impression it was the boys who came in for that."

For a moment Ibach did not seem to see the point. Then, suddenly, with a shout: "By Jimminy, dat is goot -- Gottlieb, one more bottle on the shentleman."

From the "shentleman": "Gottlieb, make it two."

"Ja wohl"!

After the fire, Ibach reestablished himself on Fifth Avenue, in the midst of a continual hurly-burly. And although Gottlieb was there to maintain traditions, and the zither was played occasionally, the old-timers sadly missed the intimate atmosphere to which they had been so long accustomed, and the old reunions somehow refused to be revived. Obviously, too much had happened in the meantime, and we were all living in another Chicago. In contrast with the glaring effrontery of the upstart new -- how soft and mellow the old, how instinct with the ineffable charm of a perfect day that is gone forever!

Do you have articles of historical interest pertaining to the zither? If so, contact us.